What Is a Break Even Analysis Explained

What Is a Break Even Analysis Explained – Ever wondered at what point your business will actually start making money? There’s a specific term for that magic number: break-even analysis.

Put simply, a break-even analysis tells you the exact point where your total sales cover your total costs. It’s that crucial moment when you stop losing money on your venture and every sale after that starts generating a profit. Think of it as the financial finish line you have to cross.

Uncovering Your Financial Turning Point

Let’s imagine you’ve just opened a small coffee shop in Manchester. You have bills that arrive like clockwork every month—rent (£2,000), insurance (£100), staff wages (£3,000)—regardless of how many lattes you sell. Then you have the costs that go up with every customer, like coffee beans, milk, and cups, which might work out to £1.10 per coffee sold.

So, the big question is: how many coffees, priced at £3.50 each, do you need to sell just to cover all of those expenses?

That’s precisely what a break-even analysis tells you. This isn’t just some dry academic exercise; it’s a practical signpost showing the minimum sales target you must hit to avoid being in the red.

Why This Number Matters

Knowing your break-even point brings a huge amount of clarity to your business strategy. It helps you figure out if your idea is even viable before you sink too much money into it or launch a new product line. It’s a fundamental tool that thousands of UK businesses rely on to make critical decisions.

For instance, data from UK small business surveys shows that a new retail startup with annual fixed costs of £20,000 and selling an item for £25 with a variable cost of £15 would need to sell 2,000 units just to break even. This insight is so vital that UK government support programmes often stress its importance; businesses that perform this analysis have been shown to cut their risk of early-stage failure by around 15%. You can dig deeper into these findings in the UK Business Data Survey 2024.

Ultimately, your break-even analysis empowers you to:

- Set realistic sales goals by giving your team a tangible, meaningful target to aim for.

- Make informed pricing decisions to ensure every sale contributes enough towards covering your costs.

- Assess financial risk when you’re thinking about new expenses, like hiring another team member or moving to a bigger office.

By identifying the point where costs and revenue are equal, you transform financial uncertainty into a clear, actionable plan. It’s the first step toward building a sustainable and profitable business.

The Building Blocks of Your Break-Even Point

Before you can work out your break-even point, you need to get your head around its three essential ingredients. Think of it like a recipe: get these components right, and the final result will be accurate and incredibly useful for making decisions. These building blocks are your fixed costs, variable costs, and the selling price of whatever it is you sell.

Getting your expenses categorised correctly is the first—and most crucial—step. A solid grasp of your numbers is fundamental to good business, and if you’re just starting out, getting familiar with small business accounting basics will put you on the right path from day one.

Understanding Your Fixed Costs

Fixed costs are the expenses that stay the same every month, no matter how much you sell. They’re the predictable, consistent bills you have to pay just to keep the lights on. Even if you had a terrible month and sold absolutely nothing, these costs would still be there, waiting to be paid.

For example, if you run a small digital marketing agency from an office in Manchester, your monthly rent of £800 is a classic fixed cost. It doesn’t change whether you land one client or ten.

Other common examples include:

- Annual insurance premiums

- Salaries for your full-time staff

- Website hosting fees

- Loan repayments

These costs form the baseline of your expenses—the total figure you must cover before you can even think about making a single penny of profit.

Identifying Your Variable Costs

Unlike their fixed cousins, variable costs move in lockstep with your sales. The more you produce or sell, the higher these costs become. If you sell nothing, your variable costs are zero. Simple as that.

Imagine you own a bakery in Bristol famous for its sourdough. The flour, yeast, and salt you use for each loaf are all variable costs. If these ingredients cost £0.80 per loaf, and you bake 100 loaves, your variable costs for that batch are £80. The more loaves you bake to meet Saturday morning demand, the more ingredients you’ll need to buy.

Key Takeaway: Variable costs are tied directly to each item sold. They represent the cost of producing one unit or delivering one service, making them a critical piece of your profitability puzzle.

To help you sort your own costs, it’s useful to see how they apply to different types of businesses.

Fixed vs Variable Costs Common UK Business Examples

The table below breaks down typical fixed and variable costs for two common UK small business models: an e-commerce store and a local cafe. Use it as a guide to start classifying your own expenses.

| Cost Type | Definition | Example for a UK E-commerce Business | Example for a UK Cafe |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Costs | Expenses that remain constant regardless of sales volume. | Monthly Shopify subscription, warehouse rent, employee salaries, website hosting. | Rent for the premises, business rates, staff salaries, insurance, POS system subscription. |

| Variable Costs | Expenses that change in direct proportion to sales volume. | Cost of goods sold (the products themselves), packaging materials, shipping fees, transaction fees. | Coffee beans, milk, sugar, takeaway cups, ingredients for cakes and sandwiches. |

Seeing your costs laid out like this makes it much easier to separate what you have to pay each month from what you only pay when you make a sale. This distinction is the bedrock of break-even analysis.

Introducing the Contribution Margin

The final piece of the puzzle is the contribution margin. This might sound a bit technical, but the concept is simple and incredibly powerful. It’s the amount of money from each sale that’s left over to help pay down your fixed costs.

You calculate it with a straightforward formula:

Selling Price Per Unit – Variable Costs Per Unit = Contribution Margin Per Unit

Let’s go back to that Bristol bakery. If a loaf of sourdough sells for £4.00 and the variable costs (flour, yeast, etc.) add up to £1.50, the contribution margin is £2.50.

This means every single loaf sold contributes £2.50 towards paying the bakery’s rent, salaries, and other fixed expenses. Once all those fixed costs are covered for the month, that £2.50 from each extra sale becomes pure profit.

How to Calculate Your Break-Even Point

Now that we’ve covered the essential ingredients, it’s time to put them together and find your break-even point. The calculation itself is surprisingly straightforward, turning all your cost data into a single, actionable target. We’ll look at the two main formulas you’ll need: one for the number of units you need to sell, and another for the total sales revenue you need to hit.

The Break-Even Formula in Units

To figure out exactly how many products you need to shift to cover your costs, we’ll use the contribution margin we talked about earlier. The formula is beautifully simple:

Fixed Costs / Contribution Margin Per Unit = Break-Even Point in Units

This calculation gives you the precise volume of sales you need to reach the point where you stop losing money. Every single unit sold after this number is pure profit.

The Break-Even Formula in Sales Revenue

Sometimes, knowing the number of units isn’t all that helpful. This is especially true for service businesses or companies selling a wide range of different products. In these cases, it’s much more useful to know the total sales revenue you need to bring in. For this, you’ll need to calculate your contribution margin ratio first.

- Contribution Margin Ratio = (Contribution Margin Per Unit / Selling Price Per Unit)

- Break-Even Point in Sales (£) = Fixed Costs / Contribution Margin Ratio

This gives you a target in pounds rather than units, which can be much easier to track against your financial goals. If you want a quick way to run the numbers, you can always use a dedicated break-even calculator to check your figures.

A Practical Example: A London Craft Brewery

Let’s bring this to life with a real-world scenario. Imagine a small craft brewery in London called “Thameside Ales.” We need to work out how many cases of their signature IPA they must sell each month just to break even.

First, let’s lay out their costs:

- Total Monthly Fixed Costs: £5,000 (this covers rent on their archway brewery, staff salaries, and insurance).

- Selling Price Per Case: £24.

- Variable Costs Per Case: £9 (this includes bottles, ingredients, packaging, and shipping).

Now, we can plug these numbers into our formulas.

- Calculate the Contribution Margin Per Case:

£24 (Selling Price) – £9 (Variable Costs) = £15 - Calculate the Break-Even Point in Units (Cases):

£5,000 (Fixed Costs) / £15 (Contribution Margin) = 334 cases (rounded up)

Thameside Ales must sell 334 cases of their IPA each month just to cover all their expenses. The 335th case sold is their first taste of actual profit.

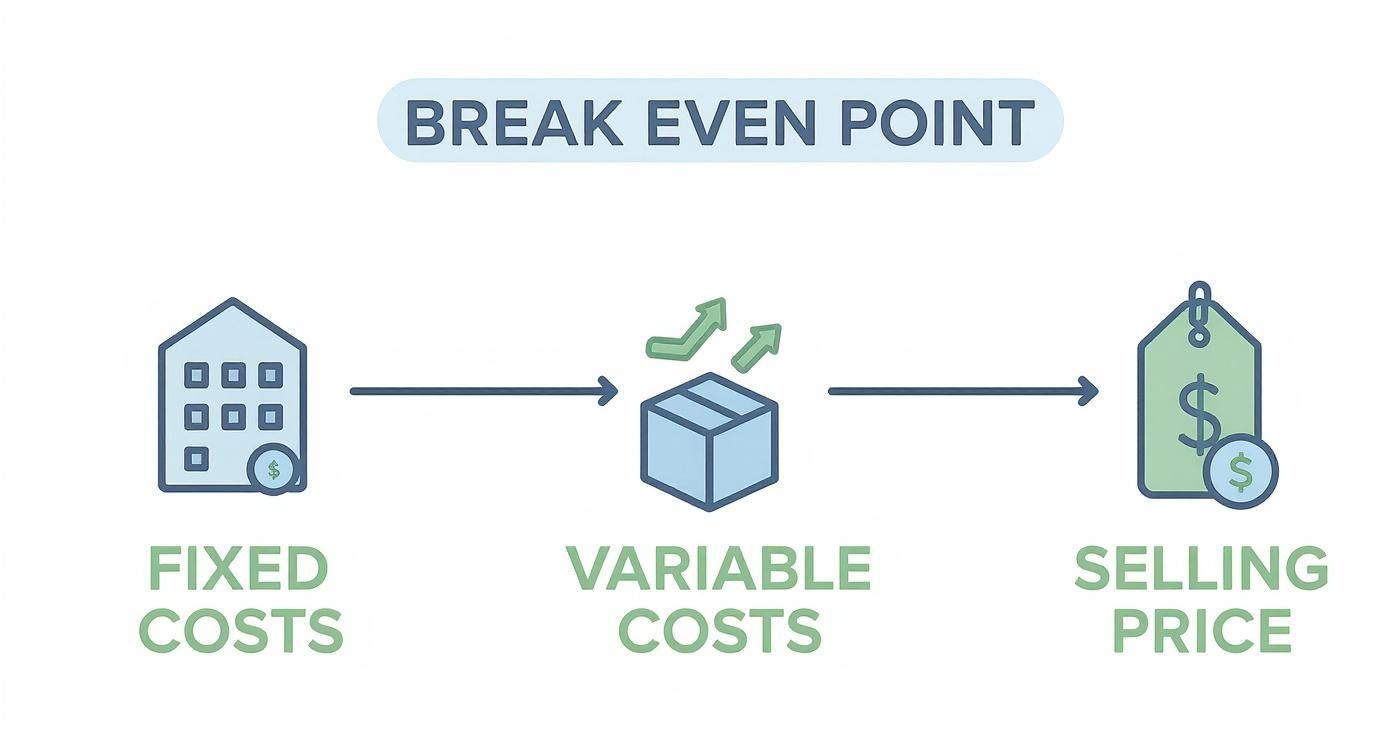

This concept map helps visualise the relationship between your fixed costs, variable costs, and selling price when working out the break-even point.

As the infographic shows, getting a handle on how these three core components interact is fundamental to pinpointing whether your business is financially viable.

Historically, this calculation has been a vital tool for UK businesses trying to navigate economic change. Following the 2008 financial crisis, for instance, over 70% of UK SMEs adopted break-even analysis to stabilise their operations. This move was directly correlated with a 10% improvement in survival rates, highlighting its enduring value as a strategy for resilience in the UK’s economic environment.

Checkout our Break Even Calculator

Break Even Analysis in the Real World

The formulas are a great starting point, but seeing break-even analysis in action is where it really clicks. It’s one thing to know the theory; it’s another to see how it applies to a real business trying to make ends meet.

While the core principles are the same for everyone, the practical application looks a bit different depending on what you sell. To make it concrete, let’s walk through two relatable scenarios for UK small businesses. First, we’ll look at a product-based business—a small, handmade cosmetics company. Then, we’ll switch gears to a service-based business—a freelance graphic designer—to see how they figure out the billable hours needed to stay afloat.

Example One: A Product-Based Business

Meet “Cornwall Organics,” a small company that makes and sells beautiful handmade soap bars. The owner is passionate about her craft, but she needs to know exactly how many bars she has to sell each month just to cover her costs. No guesswork, just a clear target.

Let’s break down her numbers:

- Total Monthly Fixed Costs: £1,200. This covers her workshop rent, website hosting, insurance, and the modest salary she pays herself. These costs stay the same whether she sells one bar or a thousand.

- Selling Price Per Soap Bar: £6.

- Variable Costs Per Soap Bar: £2.50. This is the cost of raw ingredients (like oils and botanicals), packaging, and the small payment processing fee she pays on every single sale.

With these figures, the first step is to work out her contribution margin—the amount each sale contributes towards paying off those fixed costs.

£6.00 (Selling Price) – £2.50 (Variable Costs) = £3.50 (Contribution Margin)

Every single bar she sells puts £3.50 in the pot to tackle that £1,200 of fixed costs. Now, we can find her break-even point in units.

£1,200 (Fixed Costs) / £3.50 (Contribution Margin) = 343 bars (rounded up)

The Verdict: Cornwall Organics must sell 343 soap bars every single month just to cover its expenses. Every bar sold after the 343rd is pure profit. That number isn’t just a metric; it’s a powerful target for the owner to focus on.

Example Two: A Service-Based Business

Now, let’s head over to Cardiff and meet a freelance graphic designer. For service businesses, the “unit” sold isn’t a physical product; it’s an hour of their time and expertise. The designer wants to figure out the minimum number of billable hours they need to work each month to break even.

Here are their monthly financials:

- Total Monthly Fixed Costs: £2,000. This covers home office expenses, professional indemnity insurance, vital design software subscriptions (like Adobe Creative Cloud), and the basic living costs drawn as a salary.

- Selling Price Per Hour: £50.

- Variable Costs Per Hour: £5. These are costs directly linked to client work, like project management software fees, transaction fees on invoices, and a small budget for project-specific assets like stock photos.

Just like with the soap maker, we start by finding the contribution margin.

£50 (Hourly Rate) – £5 (Variable Costs) = £45 (Contribution Margin per Hour)

So, each billable hour contributes £45 towards the designer’s fixed monthly costs. Let’s calculate the break-even point in hours.

£2,000 (Fixed Costs) / £45 (Contribution Margin) = 45 hours (rounded up)

The designer needs to bill for 45 hours of work each month simply to cover all their costs. This is their baseline for survival. Knowing this gives them a clear, minimum target, helping them plan their workload and understand that any time billed beyond this point is what builds their profit and grows the business.

Break Even Scenarios: Product vs Service Business

These two examples show just how flexible break-even analysis is. Whether you’re selling a physical item or your time, the logic holds. The table below gives you a side-by-side look at how the metrics differ between a product and a service model.

| Metric | UK Product Business (Soap Maker) | UK Service Business (Graphic Designer) |

|---|---|---|

| Unit of Sale | One soap bar | One billable hour |

| Selling Price | £6.00 per bar | £50.00 per hour |

| Variable Costs | £2.50 per bar (ingredients, packaging) | £5.00 per hour (software fees, assets) |

| Contribution Margin | £3.50 per bar | £45.00 per hour |

| Fixed Costs | £1,200 per month | £2,000 per month |

| Break-Even Point | 343 bars per month | 45 hours per month |

As you can see, the ‘unit’ is the biggest difference, but the goal is the same: find that magic number where revenue perfectly covers costs. For any entrepreneur, this isn’t just an accounting exercise—it’s the first major milestone on the road to profitability.

Using Break-Even Analysis for Smarter Decisions

Knowing your break-even point is enlightening, but its real power is unlocked when you use it as a dynamic tool for decision-making. It transforms from a static number into a strategic compass, helping you map out the financial impact of future choices before you commit.

Ultimately, this analysis helps you answer the tough “what-if” questions that every business owner faces. By running different scenarios, you can confidently assess risks and opportunities, bringing hard data into conversations that might otherwise be driven by gut feeling alone. It’s what keeps you agile and ensures your choices support long-term stability and growth.

Modelling Future Scenarios

One of the most valuable ways to use break-even analysis is to test the financial effects of big business changes. By tweaking the components of your formula—fixed costs, variable costs, or price—you can see exactly how a decision will alter your path to profitability.

Let’s use our “Cornwall Organics” soap business as a practical example. The owner is considering hiring a part-time assistant for £600 per month.

- Old Fixed Costs: £1,200

- New Fixed Costs: £1,200 + £600 = £1,800

- Contribution Margin: £3.50 (this hasn’t changed)

- New Break-Even Point: £1,800 / £3.50 = 515 bars (rounded up)

Suddenly, she needs to sell an extra 172 soap bars every month just to cover the new salary. This calculation doesn’t say “don’t hire”; it asks, “Can this new hire help us sell at least 172 more bars per month?”

Other common scenarios include:

- Investing in new equipment: If a new soap mould reduces waste, the variable cost per bar might drop from £2.50 to £2.20. This increases the contribution margin to £3.80 and lowers the break-even point, showing how quickly the investment could pay for itself.

- Moving to a larger workshop: If the rent increases fixed costs by £400, the new break-even point would be (£1,200 + £400) / £3.50 = 458 bars.

By forecasting the impact of these changes, you can make strategic investments with a clear understanding of the sales performance needed to support them. This forward-looking approach is a cornerstone of effective financial management. A detailed guide on how to create a cash flow forecast can further strengthen your ability to plan for these future financial shifts.

Making Strategic Pricing Decisions

Pricing is another area where break-even analysis truly shines, especially when you’re thinking about running a sale or offering discounts. A lower price directly shrinks your contribution margin per unit, which can dramatically increase the number of items you need to sell just to cover your costs.

Let’s say Cornwall Organics wants to run a 10% off sale, reducing the soap bar price from £6.00 to £5.40.

- New Selling Price: £5.40

- Variable Costs: £2.50 (these stay the same)

- New Contribution Margin: £5.40 – £2.50 = £2.90

- New Break-Even Point: £1,200 / £2.90 = 414 bars

The business now needs to sell 71 more bars (414 vs 343) just to break even during the sale period. This simple calculation prevents you from accidentally launching a promotion that actually costs you money. It helps you ask the right question: “Is this sale likely to increase our monthly sales by more than 20%?”

When to Look Beyond Break-Even Analysis

While it’s a brilliant tool, your break-even analysis isn’t a crystal ball for your business finances. Its greatest strength—simplicity—is also its biggest weakness. It gives you a static snapshot in time, working on the assumption that your costs and prices will stay perfectly consistent.

But we all know the real world isn’t that neat.

This model doesn’t factor in market swings, seasonal dips in demand, or that dreaded email from a supplier announcing a price hike. If your material costs suddenly jump, your original break-even point becomes obsolete overnight. The calculation also assumes every single unit you sell goes for the same price, completely ignoring things like bulk discounts or promotional sales.

Understanding Its Place in Your Strategy

The limits of a break-even analysis really start to show when your business has more moving parts.

- Multiple Products: If you sell a whole range of items, all with different prices and profit margins, a single break-even point can be seriously misleading. To get an accurate picture, you’d need to calculate a weighted average based on your sales mix—something that can change from one week to the next.

- Economies of Scale: The analysis assumes your variable costs per unit are fixed. But as your business grows, you’ll likely benefit from economies of scale. Buying in bulk might lower your cost per unit, which in turn changes your entire break-even dynamic.

A break-even analysis is a foundational tool, not the final word. Think of it as your starting point. It’s designed to give you a crucial baseline, but it absolutely must be used alongside other financial tools like cash flow forecasting and profit and loss statements for a truly well-rounded view of your business’s health.

Got Questions? We’ve Got Answers

Getting to grips with break-even analysis is the first big step, but it often brings up more specific questions. Let’s tackle some of the most common ones that business owners ask.

What’s the Difference Between Break-Even Point and Payback Period?

It’s easy to mix these two up, but they tell you very different things.

Think of it like this: your break-even point is all about profitability. It tells you the exact moment—in terms of sales or units sold—when you stop losing money and start making it. It’s the tipping point from red to black.

The payback period, on the other hand, is purely about cash flow and time. It answers the question, “How long will it take to get my initial investment back?” It doesn’t care about profit, only how quickly your cash outlay is returned.

How Often Should I Calculate My Break-Even Point?

Your break-even point isn’t a “set it and forget it” number. You should run the numbers again anytime your key variables shift.

As a general rule, a quarterly review is good practice. But it becomes absolutely essential when you’re facing a big decision. Thinking about hiring new staff, launching a new product, or changing your prices? That’s the perfect time to recalculate and see how it impacts your bottom line.

Can I Use This for a Business with Multiple Products?

Yes, you absolutely can, but it requires one extra calculation. You can’t just analyse each product in isolation; you need to find a single break-even point for the entire business.

To do this, you calculate a weighted average contribution margin. This is based on your expected sales mix. For instance, if you predict Product A will make up 60% of your sales and Product B will make up the other 40%, you’d weight their individual contribution margins accordingly. This gives you a blended margin that reflects how your business actually makes money, allowing you to find a single, unified break-even point.

At Grow My Acorn, we provide the essential information and advice that entrepreneurs and small business owners need to succeed. From financial planning to growth strategies, we’re here to help you build a thriving business. Find out more at https://growmyacorn.co.uk.